Ancient Egyptian race controversy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the "history of the controversy" about the race of the ancient Egyptians. For discussion of the scientific evidence relating to the race of the ancient Egyptians, see Population history of Egypt.

Current scholarly consensus holds that the concept of "pure race" is incoherent[2] and that applying modern notions of race to ancient Egypt is anachronistic.[3] However, the issue of the race of the ancient Egyptians continues to be debated in the public arena, with particular focus on the race of specific notable individuals from Dynastic times, including Tutankhamun,[4] Cleopatra VII,[5][6][7] and also the model for the Great Sphinx of Giza.[8][9]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Origins of the controversy

The earliest examples of disagreement in modern times, regarding the race of the ancient Egyptians, occurred in the work of Europeans and Americans early in the 19th century. For example, in an article published in the New-England Magazine of October 1833, the authors dispute a claim that the Ancient Egyptians “were adduced, affirmed to be Ethiopians.” Among other things, they point out (at pg 275), with reference to tomb paintings: “It may be observed that the complexion of the men is invariably red, that of the women yellow; but neither of them can be said to have anything in their physiognomy at all resembling the Negro countenance.” And (at pg 276) they state, with reference to the Sphinx: “The features are Nubian, or what, from ancient representations, may be called Ancient Egyptian, which is quite different from the Negro features.”[10]In his Principes Physiques de la Morale, Déduits de l'Organisation de l'Homme et de l'Univers, Constantin-François Chassebœuf writes that "The Copts are the proper representatives of the Ancient Egyptians" due to their "jaundiced and fumed skin, which is neither Greek nor Arab, their full faces, their puffy eyes, their crushed noses, and their thick lips."[11]

Just a few years later, in 1839, Champollion states in his work "Egypte Ancienne" that the Egyptians and Nubians are represented in the same manner in tomb paintings and reliefs and that "The first tribes that inhabited Egypt, that is, the Nile Valley between the Syene cataract and the sea, came from Abyssinia to Sennar. In the Copts of Egypt, we do not find any of the characteristic features of the Ancient Egyptian population. The Copts are the result of crossbreeding with all the nations that successfully dominated Egypt. It is wrong to seek in them the principal features of the old race."[12]

[edit] Slavery in the USA

In the early 19th century, slavery in the United States was still being justified, based in part on the assumption that black people were intellectually inferior, and pro-slavery advocates were thus unreceptive to any suggestion of advanced black civilizations. In 1844, Samuel George Morton, a proslavery supporter and one of the pioneers of scientific racism and polygenism, published his book Crania Aegyptica with the intention of “proving” that the Ancient Egyptians were not black.[13] In 1855 George Gliddon and Josiah C. Nott published Types of Mankind with the same intention.[14] All three authors concluded that Egyptians were intermediate between the African and Asiatic races. They acknowledged that Negroes were present in ancient Egypt but claimed they were either captives or servants.[15][edit] Dynastic race theory

Main article: Dynastic race theory

In the early 20th century, Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, one of the leading Egyptologists of his day, noted that the skeletal remains found at pre-dynastic sites at Naqada (Upper Egypt) showed marked differentiation. Together with cultural evidence, such as architectural styles, pottery styles, cylinder seals, and numerous rock and tomb paintings, he deduced that a Mesopotamian force had invaded Egypt in predynastic times, imposed themselves on the local Badarian (African) people, and become their rulers. This came to be called the “Dynastic Race Theory.”[16][17] The theory further argued that the Mesopotamians then conquered both Upper and Lower Egypt and founded the First Dynasty.In the 1950s, the Dynastic Race Theory was widely accepted by mainstream scholarship, and the Ancient Egyptians were, therefore, considered to be “Asiatic” or “Semitic” rather than "African" or "Hamitic." Early Afrocentrists, such as the Senegalese Egyptologist Cheikh Anta Diop, fought against the Dynastic Race Theory with their own "Black Egyptian" theory and claimed, among other things, that European scholars supported the Dynastic Race Theory to avoid having to admit that Ancient Egyptians were black.[18] Bernal proposed that the Dynastic Race theory was conceived by so-called Aryan scholars to deny Egypt its African roots,[19] and modern Afrocentrists continue to condemn the alleged dividing of African peoples into racial clusters as being new versions of the Dynastic Race Theory and the Hamitic hypothesis.[20]

In the aftermath of World War II, Super Race theories became unpalatable. In addition, more modern technologies allowed the investigation of the DNA of the Egyptian peoples, and it was concluded that the Egyptian civilization has been a local indigenous development all along.[17][21][22][23] However, the Dynastic Race Theory had always accepted that the original people of Ancient Egypt were “of predominantly Negroid type,” and the debate was really about whether or not the “civilization” was inspired by outsiders.[24]

[edit] Afrocentrism

The roots of afrocentrism lay in the repression of blacks throughout the Western world in the 19th century, particularly in the United States.[25] At the turn of the century, however, there came a rise in black racial consciousness as a tool to overcome oppression. Part of this reaction involved a focus on black history and counteracting what was perceived as white, eurocentric history in favor of an historical narrative of Europe (and what was viewed as its founding culture, ancient Greece) that gave blacks a more prominent role.[26] During the European colonial era on the African continent, the prevalent European attitude was that ancient Egyptians were 'white,' as the French scholar Alain Froment shows on the basis of two encyclopedias from the 1930s.[27]Specifically, this attempted rewriting of the historical narrative of Europe by some individuals developed into two main forms: the claim that European civilization was founded, not by the Greeks, but by the Egyptians, whose culture and learning the Greeks allegedly stole and that the Egyptians themselves were not only African but also black.[28] Some Afrocentrists link the two claims, as the following quote (by Marcus Garvey) displays:

| “ | Every student of history, of impartial mind, knows that the Negro once ruled the world, when white men were savages and barbarians living in caves; that thousands of Negro professors at that time taught in the universities in Alexandria, then the seat of learning; that ancient Egypt gave the world civilization and that Greece and Rome have robbed Egypt of her arts and letters, and taken all the credit to themselves.[29] | ” |

Although questions surrounding the race of the ancient Egyptians had occasionally arisen in 18th and 19th-century Western scholarship. as part of the growing interest in attempted scientific classifications of race, in academia, the idea was popularized and continued throughout the 20th century in the works of George James, Cheikh Anta Diop, and to an extent in Martin Bernal's Black Athena. All three have used the terms "black," "African," and "Egyptian" interchangeably,[30] despite what Snowden calls "copious ancient evidence to the contrary."[31]

While at the University of Dakar, Diop tried to establish the skin color of the Egyptian mummies by measuring the melanin content of the skin, stating: “In practice it is possible to determine directly the skin color and, hence, the ethnic affiliations of the ancient Egyptians by microscopic analysis in the laboratory; I doubt if the sagacity of the researchers who have studied the question has overlooked the possibility.”[32] Diop further attempted to link Egypt to Senegal by arguing that the Ancient Egyptian language was related to his native Wolof.[33]

Diop's work was well received by the political establishment in the post-colonial formative phase of the state of Senegal, and by the Pan-Africanist Négritude movement. Diop participated in a UNESCO symposium in Cairo in 1974, where he presented his "Black Egyptian" theory, but it received little support from the other delegates. He was, however, invited to write the chapter on the "origins of the Egyptians" in the UNESCO General History of Africa.[34]

Founded in 1979, the Journal of African Civilizations has continually advocated that Egypt should be viewed as a black civilization.[35][36] The group centering around the journal include Ivan van Sertima and J.H. Clarke (who has advanced further the "Cleopatra was black" theory). Other notable proponents of the meme include Chancellor Williams.[37] Mainstream scholarship has generally been critical of the journal: J.D. Muhly describes it as "well-intentioned but quite unconvincing and lacking in the basic techniques of critical scholarship."[38]

The British Africanist Basil Davidson summarized the issue as follows:

Whether the Ancient Egyptians were as black or as brown in skin color as other Africans may remain an issue of emotive dispute; probably, they were both. Their own artistic conventions painted them as pink, but pictures on their tombs show they often married queens shown as entirely black, being from the south (from what a later world knew as Nubia): while the Greek writers reported that they were much like all the other Africans whom the Greeks knew.[39]

[edit] Modern scholarship

Modern scholars who have studied Ancient Egyptian culture and population history have responded to the controversy over the race of the Ancient Egyptians in different ways. Dr. Zahi Hawass, the current Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, has stated that "The portrayal of ancient Egyptian civilization as black has no element of truth to it;" and that "Ancient Egyptians are not Arabs and are not Africans despite the fact that Egypt is in Africa." [40][41] Other academics in various fields contend that Ancient Egypt was fundamentally an African civilization, with cultural and biological connections to Egypt's African neighbors.[42] Several anthropologists who study the biological relationships of the Ancient Egyptian population call for a recognition of Africa's genetic diversity when considering the racial identity of the Ancient Egyptians.[43]Because race is not considered a valid scientific concept by most modern scientists, the focus of some experts who study population biology has whether or not the Ancient Egyptians were primarily biologically African, rather than which race they belonged to.[44]

In 1996, the Indianapolis museum of art curator, Theodore Celenko, held an exhibition titled Egypt in Africa in order to present works of art that emphasized Egypt's cultural connection to the rest of the African continent.[42] A collection of essays was formed into a book published under the same name, edited by Celenko, which included contributions from leading experts in various fields including archaeology, art history, physical anthropology, African studies, Egyptology, Afrocentric studies, linguistics, and classical studies. Among the contributors were Chike Aniakor, Molefi Kete Asante, Robert Steven Bianchi, Arthur P. Bourgeois, Shomarka Keita, Christopher Ehret, Chapurukha M. Kusimba, Frank M. Snowden, Jr., and Frank J. Yurco. While the contributors differed in some opinions, the consensus of the authors was that Ancient Egypt was and should be considered an African civilization.[45]

[edit] Specific current-day controversies

The most recent specific conference on the race of the ancient Egyptians was at UNESCO’s international Cairo Symposium in 1974, where more than 20 recognized international scholars debated, among other things, the race of the founders of ancient Egyptian civilization. The majority view was that the ancient Egyptians were neither black nor white, as per current terminology.[46][47] In recent times, the issues regarding the race of the ancient Egyptians “are troubled waters which most people who write about ancient Egypt from within the mainstream of scholarship avoid.”[24] The ongoing debate, therefore, takes place mainly in the public sphere and tends to focus on a small number of specific issues.[edit] Tutankhamun

See also: Tutankhamun

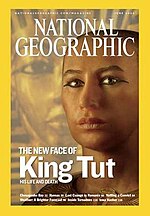

Supporters of Afrocentrism have claimed that Tutankhamun was black, and have protested that attempted reconstructions of Tutankhamun's facial features (as depicted on the cover of National Geographic Magazine) have represented the king as “too white”.[48]Forensic artists and physical anthropologists from Egypt, France, and the United States independently created busts of Tutankhamun, using a CT-scan of the skull. Biological anthropologist Susan Anton, the leader of the American team, said the race of the skull was “hard to call.” She stated that the shape of the cranial cavity indicated an African, while the nose opening suggested narrow nostrils, which is usually considered to be a European characteristic. The skull was thus concluded to be that of a North African.[49] Other experts have pointed out that neither skull shapes nor nasal openings are a reliable indication of race.[50]

Although modern technology can reconstruct Tutankhamun's facial structure with a high degree of accuracy, based on CT data from his mummy,[51][52] determining his skin tone and eye color is impossible. The clay model was therefore given a flesh coloring which, according to the artist, was based on an "average shade of modern Egyptians."[53]

Terry Garcia, National Geographic's executive vice president for mission programs, said, in response to some of those protesting against the Tutankhamun reconstruction:

The big variable is skin tone. North Africans, we know today, had a range of skin tones, from light to dark. In this case, we selected a medium skin tone, and we say, quite up front, 'This is midrange.' We will never know for sure what his exact skin tone was or the color of his eyes with 100% certainty. ... Maybe in the future, people will come to a different conclusion.[54]When pressed on the issue by American activists in September 2007, the current Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, Dr. Zahi Hawass stated that "Tutankhamun was not black, and the portrayal of ancient Egyptian civilization as black has no element of truth to it;" Hawass further observed that "[Ancient] Egyptians are not Arabs and are not Africans despite the fact that Egypt is in Africa." [40] [41]

Ahmed Saleh, the former archaeological inspector for the Supreme Council of antiquities stated that the procedures used in the facial re-creation made Tut look Caucasian, "disrespecting the nation's African roots."[55]

In a November 2007 publication of Ancient Egypt Magazine, Hawass asserted that none of the facial reconstructions resemble Tut and that, in his opinion, the most accurate representation of the boy king is the mask from his tomb.[56] The Discovery Channel commissioned a facial reconstruction of Tutankhamun, based on CT scans of a model of his skull, back in 2002.[57][58]

[edit] Cleopatra VII

Further information: Cleopatra VII

Cleopatra's race and skin color have also caused frequent debate, as described in an article from The Baltimore Sun.[5] There is also an article entitled: Was Cleopatra Black? from Ebony magazine,[6] and an article about Afrocentrism from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that mentions the question, too.[7] Scholars generally suggest a light olive skin color for Cleopatra, based on the following facts: her Macedonian family had intermingled with the Persian aristocracy of the time; her mother's identity is uncertain,[59] and that her paternal grandmother is not known for certain.[60] Afrocentric assertions of Cleopatra's blackness have, however, continued.The question was the subject of a heated exchange between Mary Lefkowitz, who has referred in her articles to a debate she had with one of her students about the question of whether Cleopatra was black, and Molefi Kete Asante, Professor of African American Studies at Temple University. In response to Not Out of Africa by Lefkowitz, Asante wrote an article entitled Race in Antiquity: Truly Out of Africa, in which he emphasized that he "can say without a doubt that Afrocentrists do not spend time arguing that either Socrates or Cleopatra were black."[61]

In 2009, a BBC documentary speculated that Arsinoe IV, the half-sister of Cleopatra VII, may have been part African and then further speculated that Cleopatra’s mother, thus Cleopatra herself, might also have been part African. This was based largely on the claims of Hilke Thür of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, who in the 1990s had examined a headless skeleton of a female child in a 20 BC tomb in Ephesus (modern Turkey), together with the old notes and photographs of the now-missing skull.[62][63] Arsinoe IV and Cleopatra VII, shared the same father (Ptolemy XII Auletes) but had different mothers.[64]

[edit] Great Sphinx of Giza

The identity of the model for the Great Sphinx of Giza is unknown.[65] Virtually all Egyptologists and scholars currently believe that the face of the Sphinx represents the likeness of the Pharaoh Khafra, although a few Egyptologists and interested amateurs have proposed several different hypotheses.Over the years, casual observers, as well as at least one forensic artist, have characterized the face of the Sphinx as "Negroid." Some Afrocentrist writers, including W.E.B. Du Bois, have claimed that the Sphinx is a statue of a black person.[66][8][67][68] One of the earliest known descriptions of a "Negroid" Sphinx is recorded in the travel notes of a French scholar, who visited in Egypt between 1783 and 1785. Constantin-François Chassebœuf[69] and French novelist Gustave Flaubert.[70] Flaubert traveled to Egypt in 1849 and recorded the following observation:

We stop before a Sphinx ; it fixes us with a terrifying stare. Its eyes still seem full of life; the left side is stained white by bird-droppings (the tip of the Pyramid of Khephren has the same long white stains); it exactly faces the rising sun, its head is grey, ears very large and protruding like a negro’s, its neck is eroded; from the front it is seen in its entirety thanks to great hollow dug in the sand; the fact that the nose is missing increases the flat, negroid effect. Besides, it was certainly Ethiopian; the lips are thick….[71]American geologist Robert M. Schoch has written that the "Sphinx has a distinctive African, Nubian, or Negroid aspect which is lacking in the face of Khafre."[9]

[edit] The meaning of 'Kemet'

| km biliteral | km.t (place) | km.t (people) | |||||||||

|

|

|

Cheikh Anta Diop[72] William Leo Hansberry,[72] and Aboubacry Moussa Lam[75] have argued that Kemite was derived from the skin color of the people of the land, which they claim was black. This claim has become a cornerstone of Afrocentric historiography,[72] but it is rejected by a strong majority of Egyptologists.[76]

[edit] Ancient Egyptian art

Ancient Egyptian tombs and temples contained thousands of paintings, sculptures, and written works, which reveal a great deal about the people of that time. However, their depictions of themselves in their surviving art and artifacts are rendered in sometimes symbolic, rather than realistic, pigments. As a result, ancient Egyptian artifacts provide sometimes conflicting and inconclusive evidence of the ethnicity of the people who lived in Egypt during dynastic times.[77][78][79][80]Manu Ampim, a professor at Merritt College specializing in African and African American history and culture, claims in the book Modern Fraud: The Forged Ancient Egyptian Statues of Ra-Hotep and Nofret, that many ancient Egyptian statues and artworks are modern frauds that have been created specifically to hide the “fact” that the ancient Egyptians were black, while authentic artworks which demonstrate black characteristics are systematically defaced or even "modified." Ampim repeatedly makes the accusation that the Egyptian authorities are systematically destroying evidence which “proves” that the ancient Egyptians were black, under the guise of renovating and conserving the applicable temples and structures. He further accuses “European” scholars of wittingly participating in and abetting this process.[81][82]

Ampim has a specific concern about the painting of the "Table of Nations" in the Tomb of Ramses III (KV11). The “Table of Nations” is a standard painting which appears in a number of tombs, and they were usually provided for the guidance of the soul of the deceased.[77][78][83] Among other things, they described the "four races of men," as follows: (translation by E.A. Wallis Budge:[83]

The first are RETH, the second are AAMU, the third are NEHESU, and the fourth are THEMEHU. The RETH are Egyptians, the AAMU are dwellers in the deserts to the east and north-east of Egypt, the NEHESU are the black races, and the THEMEHU are the fair-skinned Libyans.The archaeologist Richard Lepsius documented many ancient Egyptian tomb paintings in his work Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien. In 1913, after the death of Lepsius, an updated reprint of the work was produced, edited by Kurt Sethe. This printing included an additional section, called the “Ergänzungsband” in German, which incorporated many illustrations that did not appear in Lepsius’ original work. One of them, plate 48, illustrated one example of each of the four “nations” as depicted in KV11, and shows the "Egyptian nation" and the "Nubian nation" as identical to each other in skin color and dress. Professor Ampim has declared that plate 48 is a true reflection of the original painting, and that it “proves” that the ancient Egyptians were identical in appearance to the Nubians, even though he admits no other examples of the "Table of Nations" show this similarity. He has further accused “Euro-American writers” of attempting to mislead the public on this issue.[84] The late Egyptologist, Dr. Frank Yurco, visited the tomb of Ramses III (KV11), and in a 1996 article on the Ramses III tomb reliefs he pointed out that the depiction of plate 48 in the Erganzungsband section is not a correct depiction of what is actually painted on the walls of the tomb. Dr Yurco notes, instead, that plate 48 is a “pastische” of samples of what is on the tomb walls, arranged from Lepsius' notes after his death, and that a picture of a Nubian person has erroneously been labeled in the pastiche as an Egyptian person. Yurco points also to the much-more-recent photographs of Dr. Erik Hornung as a correct depiction of the actual paintings.[85] (Erik Hornung, “The Valley of the Kings: Horizon of Eternity”, 1990). Ampim nonetheless continues to claim that plate 48 shows accurately the images which stand on the walls of KV11, and he categorically accuses both Yurco and Hornung of perpetrating a deliberate deception for the purposes of misleading the public about the true race of the Ancient Egyptians.[84]

[edit] The Land of Punt

The ancient Egyptians viewed the Land of Punt (Pun.t; Pwenet; Pwene) as their ancestral homeland.[86][87][88] In his book “The Making of Egypt” (1939), W. M. Flinders Petrie stated that the Land of Punt was “sacred to the Egyptians as the source of their race.” E.A. Wallis Budge stated that “Egyptian tradition of the Dynastic Period held that the aboriginal home of the Egyptians was Punt…”[89]The consensus view among the majority of Egyptologists is summed up by Ian Shaw in the Oxford History of Ancient Egypt:

| “ | There is still some debate regarding the precise location of Punt, which was once identified with the region of modern Somalia. A strong argument has now been made for its location in either southern Sudan or the Eritrean region of Ethiopia, where the indigenous plants and animals equate most closely with those depicted in the Egyptian reliefs and paintings.[90] | ” |

Other scholars disagree with this view and point to a range of ancient Egyptian inscriptions which unambiguously locate Punt in Arabia. Dimitri Meeks has written that “Texts locating Punt beyond doubt to the south are in the minority, but they are the only ones cited in the current consensus about the location of the country. Punt, we are told by the Egyptians, is situated – in relation to the Nile Valley – both to the north, in contact with the countries of the Near East of the Mediterranean area, and also to the east or south-east, while its furthest borders are far away to the south. Only the Arabian Peninsula satisfies all these indications.”[95]

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Edith Sanders: The Hamitic hypothesis: its origin and functions in time perspective, The Journal of African History, Vol. 10, No. 4 (1969), pp. 521-532

- ^ Bard, in turn citing B.G. Trigger, "Nubian, Negro, Black, Nilotic?", in African in Antiquity, The Arts of Nubian and the Sudan, vol 1, 1978.

- ^ Frank M. Snowden Jr., Bernal's 'Blacks' and the Afrocentrists: "[The ancient] Egyptians, Greeks and Romans attached no special stigma to the color of the skin and developed no hierarchical notions of race whereby highest and lowest positions in the social pyramid were based on color." Black Athena Revisited, p. 122

- ^ Tutankhamun was not black: Egypt antiquities chief, AFP, September 2007

- ^ a b Baltimore Sun: "Was Cleopatra Black", 2002

- ^ a b "Was Cleopatra Black?", from Ebony magazine, February 1, 2002. In support of this, she cites a few examples, one of which is a chapter entitled "Black Warrior Queens," published in 1984 in Black Women in Antiquity, part of the Journal of African Civilization series. It draws heavily on the work of J.A. Rogers.

- ^ a b "Afrocentric View Distorts History and Achievement by Blacks", from the St. Louis Dispatch, February 14, 1994.

- ^ a b Irwin, Graham W. (1977). Africans abroad, Columbia University Press, p. 11

- ^ a b [1]

- ^ http://digital.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=nwen;cc=nwen;rgn=full%20text;idno=nwen0005-4;didno=nwen0005-4;view=image;seq=00281;node=nwen0005-4%3A1

- ^ Volney, Constantin-François. Principies Physiques de la Morale, Deduits de l'Organisation de l'Homme et de l'Univers. Page 131

- ^ Champollion-Figeac, Egypte Ancienne. Paris: Collection L'Univers, 1839, p.27

- ^ Trafton, Scott (2004). Egypt Land: Race and Nineteenth-century American Egyptomania. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822333627. http://books.google.com/books?id=YHgv011kWIAC&printsec=frontcover#PPP1,M1.

- ^ General Remarks on "Types of Mankind"

- ^ Morton, Samuel George (1844). "Egyptian Ethnography". http://books.google.com/books?id=t1MGAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover#PPA4,M1.

- ^ Black Athena revisited, by Mary R. Lefkowitz, Guy MacLean Rogers, pg65 :: http://books.google.com/books?id=97jwg1Xwpj0C&pg=PA65&lpg=PA65&dq=%2B%22dynastic+race+theory%22,+%2Bpetrie&source=bl&ots=ZRI64NiDsF&sig=n1JXM0vMESuA04qKW8me7HZD074&hl=en&ei=rzOdSu3lDc2c8Qb6rdHGBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3#v=onepage&q=%2B%22dynastic%20race%20theory%22%2C%20%2Bpetrie&f=false

- ^ a b Early dynastic Egypt, by Toby A. H. Wilkinson, pg 15

- ^ Epic encounters: culture, media, and U.S. interests in the Middle East – 1945-2000 by Melani McAlister

- ^ Black Athena revisited, by Mary R. Lefkowitz, Guy MacLean Rogers

- ^ History of Philosophy (3 Vols. Set), by William Turner, pg 8

- ^ Prehistory and Protohsitory of Egypt, Emile Massoulard, 1949

- ^ Yurco, “Black Athena Revisited”, by Mary R. Lefkowitz, Guy MacLean Rogers

- ^ Sonia R. Zakrzewski: Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state - Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton, Highfield, Southampton (2003)

- ^ a b Ancient Egypt: anatomy of a civilization, by Barry J. Kemp, pg 47

- ^ Bard p.106

- ^ lefkowtiz p. 7

- ^ Froment 1994, p. 38

- ^ Lefkowitz p. 8

- ^ Marcus Garvey: "Who and what is a Negro," 1923. Quoted by Lefkowitz.

- ^ Snowden p.116 of Black Athena Revisited.

- ^ Snowden p. 116

- ^ Chris Gray, Conceptions of History in the Works of Cheikh Anta Diop and Theophile Obenga, (Karnak House:1989) 11-155

- ^ Alain Ricard, Naomi Morgan, The Languages & Literatures of Africa: The Sands of Babel, James Currey, 2004, p.14

- ^ UNESCO, "Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script; Proceedings," (Paris: 1978), pp. 3-134

- ^ Snowden p. 117

- ^ Homepage of the Journal of African Civilizations

- ^ Snowden pp.117-120

- ^ Muhly: "Black Athena versus Traditional Scholarship," Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 3, no 1: 83-110

- ^ Davidson, Basil (1991). African Civilization Revisited: From Antiquity to Modern Times. Africa World Press.

- ^ a b "Egyptology News» Blog Archive » Hawass says that Tutankhamun was not black". Touregypt.net. 2007-09-26. http://touregypt.net/teblog/egyptologynews/?p=2929. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ a b http://www.thedailynewsegypt.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=9519

- ^ a b Finally in Africa? Egypt, from Diop to Celenko

- ^ S.O.Y Keita & A.J. Boyce: "The Geographical Origins and Population Relationships of Early Ancient Egyptians", Egypt in Africa, (1996), pp. 25-27

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita (1995). Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships. doi:10.1007/BF02444602. http://wysinger.homestead.com/keita-1993.pdf.

- ^ Ancient Egyptian Origins

- ^ General history of Africa, by G. Mokhtar, International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa, Unesco

- ^ Afrocentrism, by Stephen Howe

- ^ King Tut Not Black Enough, Protesters Say

- ^ Washington Post: A New Look at King Tut

- ^ Skull Indices in a Population Collected From Computed Tomographic Scans of Patients with Head Trauma.

- ^ "discovery reconstruction". http://dsc.discovery.com/anthology/unsolvedhistory/kingtut/face/facespin.html.

- ^ Science museum images

- ^ King Tut's New Face: Behind the Forensic Reconstruction

- ^ Henerson, Evan (June 15, 2005). "King Tut's skin colour a topic of controversy". U-Daily News — L.A. Life. http://u.dailynews.com/Stories/0,1413,211~23523~2921859,00.html. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- ^ Mike Boehm Eternal Egypt is his business, Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, Calif.: Jun 20, 2005

- ^ Ancient Egypt Magazine, Issue 44, October / November 2007, Meeting Tutankhamun. AFP (Ancient Egypt Magazine). [2] Ancient Egypt Magazine, Issue 44, October / November 2007

- ^ http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tutmask.jpg

- ^ Tutankhamun: beneath the mask

- ^ Tyldesley, p. 30, suggests Cleopatra V as the most likely candidate.

- ^ Tyldesley p. 32

- ^ Race in Antiquity: Truly Out of Africa By Molefi Kete Asante

- ^ Foggo, Daniel (2009-03-15). "Found the sister Cleopatra killed". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/middle_east/article5908494.ece. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ Cleopatra's mother 'was African' - BBC (2009)

- ^ ”The Lives of Cleopatra and Octavia”, By Sarah Fielding, Christopher D. Johnson, pg154, Bucknell University Press, ISBN 0838752578, 9780838752579

- ^ Hassan, Selim (1949). The Sphinx: Its history in the light of recent excavations. Cairo: Government Press, 1949.

- ^ The Negro, by W. E. B. Du Bois

- ^ Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt (1915). The Negro. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1915).

- ^ Black man of the Nile and his family, by Yosef Ben-Jochannan, pg 109-110

- ^ Constantin-François Chassebœuf saw the Sphinx as "typically negro in all its features"; Volney, Constantin-François de Chasseboeuf, Voyage en Egypte et en Syrie, Paris, 1825, page 65

- ^ "...its head is grey, ears very large and protruding like a negro’s...the fact that the nose is missing increases the flat, negroid effect. Besides, it was certainly Ethiopian; the lips are thick.." Flaubert, Gustave. Flaubert in Egypt, ed. Francis Steegmuller. (London: Penguin Classics, 1996). ISBN 9780140435825.

- ^ Gustave Flaubert, Francis Steegmüller (1996). Flaubert in Egypt, ISBN 9780140435825, p. 55

- ^ a b c d e Shavit 2001: 148

- ^ Kemp, Barry J.. Ancient Egypt: Anatomy Of A Civilization. Routledge. pp. 21. ISBN 978-0415063463. http://books.google.com/books?id=l-t5vWHAVN0C&pg=PA21&ots=Whio1cbGsZ&dq=egypt+black+soil&sig=jmy3OWcilcwPoYZYgfbO2LU5_B8#PPA21,M1.

- ^ Raymond Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2002, p. 286.

- ^ Aboubacry Moussa Lam, "L'Égypte ancienne et l'Afrique", in Maria R. Turano et Paul Vandepitte, Pour une histoire de l'Afrique, 2003, pp. 50 &51

- ^ Bard, Kathryn A. "Ancient Egyptians and the Issue of Race". in Lefkowitz and MacLean rogers, p. 114

- ^ a b http://www.egyptologyonline.com/book_of_gates.htm

- ^ a b http://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/bookgates5.html

- ^ Charlotte Booth,The Ancient Egyptians for Dummies (2007) p. 217

- ^ Biological and Ethnic Identity in New Kingdom Nubia

- ^ “Ra-Hotep and Nofret: Modern Forgeries in the Cairo Museum?” pp. 207-212 in Egypt: Child of Africa (1994), edited by Ivan Van Sertima.

- ^ http://manuampim.com/

- ^ a b http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/gate/gate20.htm

- ^ a b http://manuampim.com/ramesesIII.htm

- ^ Frank Yurco, "Two Tomb-Wall Painted Reliefs of Ramesses III and Sety I and Ancient Nile Valley Population Diversity," in “Egypt in Africa” (1996), ed. by Theodore Celenko.

- ^ Briggs, Philip (2006). Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781841621289. http://books.google.com/books?id=oPAUxFDrQaQC&printsec=frontcover#PPA21,M1.

- ^ A short history of the Egyptian people. J. M. Dent. 1914. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZwlFAAAAIAAJ&printsec=titlepage#PPA10,M1.

- ^ White, Jon Manchip., Ancient Egypt: Its Culture and History (Dover Publications; New Ed edition, June 1, 1970), p. 141. "It may be noted that the ancient Egyptians themselves appear to have been convinced that their place of origin was African rather than Asian. They made continued reference to the land of Punt as their homeland."

- ^ Short History of the Egyptian People, by E. A. Wallis Budge

- ^ The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Ian Shaw, p. 317, 2003

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=jcpQqkHr328C&printsec=frontcover#PPA13,M1

- ^ Hatshepsut's Temple at Deir El Bahari By Frederick Monderson

- ^ Shaw & Nicholson, p.231.

- ^ Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- ^ Dimitri Meeks - Chapter 4 - “Locating Punt” from the book “Mysterious Lands”, by David B. O'Connor and Stephen Quirke.

[edit] References

- Mary R. Lefkowitz: "Ancient History, Modern Myths", originally printed in The New Republic, 1992. Reprinted with revisions as part of the essay collection Black Athena Revisited, 1996.

- Kathryn A. Bard: "Ancient Egyptians and the issue of Race", Bostonia Magazine, 1992: later part of Black Athena Revisited, 1996.

- Frank M. Snowden, Jr.: "Bernal's "Blacks" and the Afrocentrists", Black Athena Revisited, 1996.

- Joyce Tyldesley: "Cleopatra, Last Queen of Egypt", Profile Books Ltd, 2008.

- Alain Froment, 1994. "Race et Histoire: La recomposition ideologique de l'image des Egyptiens anciens." Journal des Africanistes 64:37-64. available online: Race et Histoire (French)

- Yaacov Shavit, 2001: History in Black. African-Americans in Search of an Ancient Past, Frank Cass Publishers

- Anthony Noguera, 1976. How African Was Egypt?: A Comparative Study of Ancient Egyptian and Black African Cultures. Illustrations by Joelle Noguera. New York: Vantage Press.

- Shomarka Keita: "The Geographical Origins and Population Relationships of Early Ancient Egyptians", Egypt in Africa, (1996), pp. 25–27

![I6 [km] km](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_I6.png)

![X1 [t] t](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_X1.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment